What You Need to Know About the NIST Guideline on Differential Privacy

#differential-privacy #pet- Highlights

- What is the current state of privacy protection

- What is Differential Privacy

- Differential Privacy Foundations

- Differential Privacy in practice

- Challenges

- Back to the basics, data protection is the paramount to privacy protection

In December 2023, NIST published its first public draft of NIST SP 800-226 Guidelines for Evaluating Differential Privacy Guarantees, this is a huge milestone of the digital privacy domain.

In this blog post, I’m going to tell you why and what you need to know from the guideline.

Highlights

I’m trying to summarize a sixty-page guideline into one blog post, but it’s still too long. So, I’m putting the highlight at the beginning for your convenience:

-

Differential Privacy (DP) is a Statistical measurement of privacy loss

-

Epsilon (ε) is an important parameter to measure the privacy loss from a data output

-

DP limits total privacy loss by setting thresholds of the ε (i.e., Privacy Budget)

-

Defining the Privacy Unit is important. (i.e., do we want to protect the privacy of a person? Or the privacy of a transaction?)

-

In practice, we add random noise to the output to meet the expected ε (or Privacy Budget)

-

-

Challenges

-

Applications are still limited to simple models (e.g., Analytic queries, simple ML models and synthetic data)

-

The reduced accuracy from added noise impacts complex analytic models a lot

-

DP on unstructured data is still very difficult

-

Bias is introduced or amplified by DP, mainly from the added noise

-

Conventional security models also apply to DP implementation. Privacy vs accuracy is an extra consideration.

-

-

Data protection and data minimization are still important fundamentals even though we have DP.

What is the current state of privacy protection

To understand the importance of Differential Privacy (DP), we first need to understand the current privacy protection approaches and some basic concepts.

Input Privacy vs Output Privacy

In the past, when people wanted to conduct research on data related to individuals, we used different methods to minimize the exposure of the raw data (e.g., Relying on a trusted 3rd party to curate the data, distributing the data curation process to different parties, etc.) These methods prevent privacy leaks from the raw data Input; we call it Input Privacy.

But in some cases, we may also want to publish the research outputs to the broader audience or even the general public. We also need to ensure that an individual’s privacy would not be derived from the result data Output; this is called the Output Privacy.

Current De-identification method doesn’t work

The main problem Differential Privacy wants to address is Output Privacy. It is about preventing individual information from being derived by combining different results and reverse engineering.

The most common method we have been using for decades is De-identification. We always talk about Personal Identifiable Information (PII), and try to remove them from raw data before doing data research.

But this method has been frequently proved vulnerable; some prominent examples include The Re-Identification of Governor William Weld’s Medical Information and De-anonymization attacks on Netflix Prize Dataset

Clearly, with enough auxiliary data, we can re-construct individual information from data that is supposed to be Anonymized. From this assumption, every piece of information about an individual should be considered PII.

What is Differential Privacy

People have been trying to define what PII is for decades and failed repeatedly. Clearly, we need a more robust framework for measuring how much privacy we’re preserving when performing anonymization.

And Differential Privacy is the framework we need. It is a Statistical measurement of how much an individual’s privacy is lost when exposing the data.

Differential Privacy is not an absolute guarantee

The guideline makes it clear at the very beginning that Differential privacy does not prevent somebody from making inferences about you.

The word Differential means that the guarantee DP provides is relative to the situation where an individual doesn’t participate in the dataset. DP can guarantee one’s privacy will not face greater risk by participating in the data, but it doesn’t mean it will have no risk at all.

Let’s consider the following example:

Medical research found that smokers have a higher risk of lung cancer, so their insurance premiums are usually higher than those of other people.

Let’s say a smoker, John, didn’t participate in that medical research; the result is probably still the same. So, no matter whether he participates or not, his insurance company can still learn that he has a higher risk of lung cancer and charge him a higher premium.

In this example, although medical research makes the insurance company know that John has higher risk of lung cancer. But we can still say DP guarantees John’s privacy in the medical research because it makes no difference to him whether he participates or not.

This is one of the first major guidelines for implementation

Although Differential Privacy has formally existed for almost 20 years, the NIST SP 800-226 guideline is probably the first guideline published by a major institution covering the considerations when implementing it.

This is a milestone in bringing DP from R&D into the discussion among practitioners and preparing us for broader adoption.

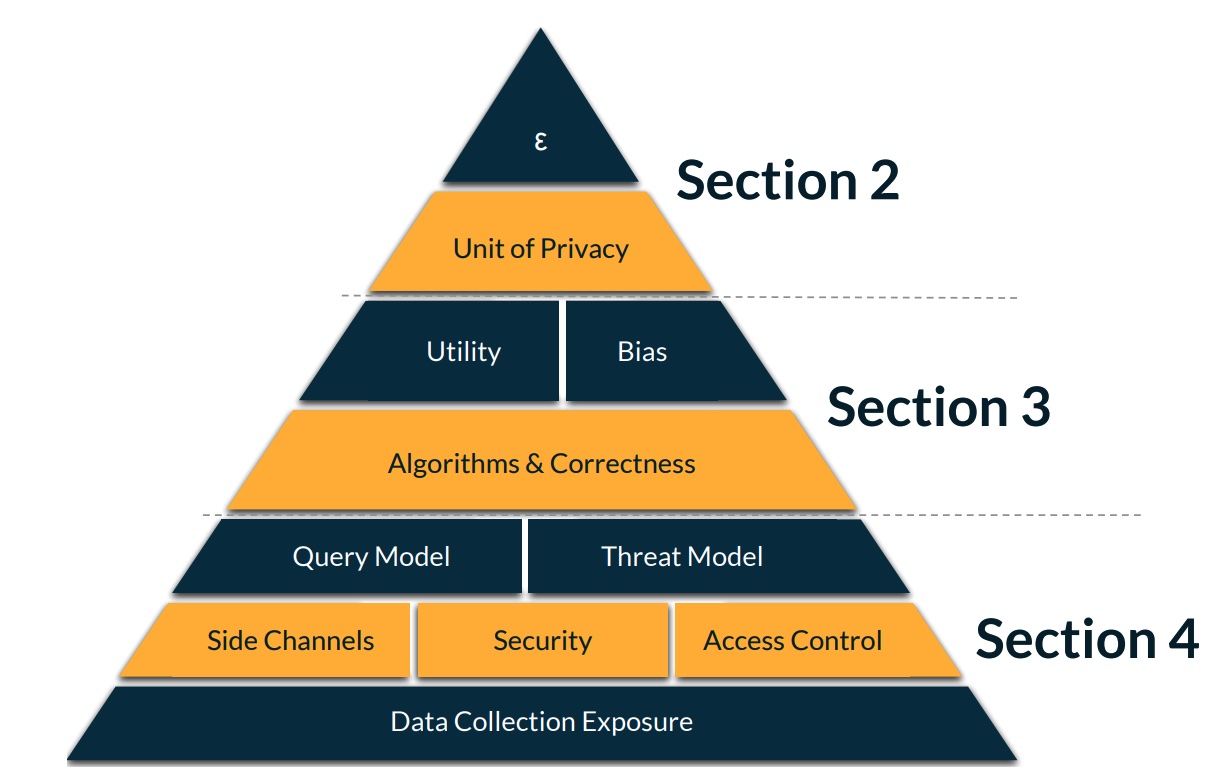

Differential Privacy Foundations

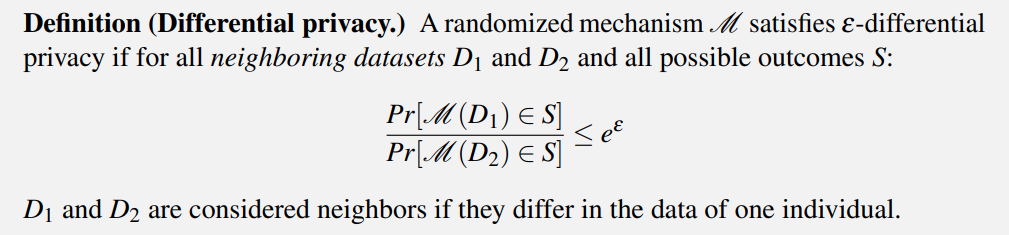

Epsilon (ε)

The formal definition of ε is the following formula:

It might be too difficult to understand, but it roughly means The chance where the datasets with and without an individual would produce different outputs.

To understand it, we can assume a very small (or even zero) ε; there is little or no difference whether an individual participates in a research. So, there’s less chance people can learn if that individual is or isn’t in the dataset.

In theory, smaller ε provide more privacy guarantee but less accuracy.

Privacy Unit

Another concept the guideline calls out is the Privacy Unit.

DP describes the difference between outputs from datasets with or without an individual, but it doesn’t define what is an individual. It can be an individual transaction, or a person.

Since the common concern of data privacy is always about people. So the guideline suggests we always use User as the Privacy Unit.

This means when we apply DP, we should always measure the ε when ALL records related to one person are presented or not.

Differential Privacy in practice

Privacy Budget to limit privacy loss

Having a mathematical measurement of privacy, we can limit privacy exposure more quantitatively.

ε represents the amount of privacy loss from an output; we can sum the ε from all the outputs published from a dataset to measure the total privacy loss.

This allows us to limit the privacy loss by setting an upper bound of the total ε allowed for all published outputs from a dataset, or we can call it the Privacy budget.

Adding noise to comply with the privacy budget

ε is defined by the difference between outputs from datasets with or without an individual; it depends on how impactful an individual is to the output.

If an individual record is very special in the dataset, the ε of one output may already exceed the total privacy budget.

So, in practice, we’ll add random noise into the output to fulfill the ε requirement.

Adding random noise lowers the difference between outputs from datasets with or without an individual, thus lowering the ε.

Challenges

Reduced accuracy and utility

Accuracy and utility of an output may be related but not necessarily the same.

The guideline calls it out by stating that output may be accurate but not useful if most attributes are redacted. Output may also be less accurate but still useful if the survey base is large.

But either way, DP impacts both the accuracy and utility of the outputs. The primary reason is the added random noise to the outputs, especially when the data size is small and more noise is required.

Applications are still limited

The guideline lists several applications of Differential Privacy; I would group them into the following 3 categories:

-

Analytic queries

This category includes most commonly used aggregation queries (e.g., Count, Summation, Min, Max, etc.)

Because the output of these queries is numbers, it’s easy to measure the privacy loss and add random noise to comply with the privacy budget.

In fact, these queries are the most commonly adopted application of DP and have the most detailed guidelines.

-

Synthetic data and Machine learning

The guideline puts these 2 into separate categories, but I would group them together to simplify things.

Generating synthetic data or training ML model from the dataset can give the curated output more correlation between attributes (The guideline uses an example of the type of coffee vs purchases’ age), which analytic queries are not good at.

There are some well-known methods for applying them to DP, like Marginal distributions and Differentially-private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD).

However, they are facing a similar problem: The accuracy and utility of the output are easily affected by the model’s complexity

The main reason is that the random noise added to the DP output will be amplified when the analysis goal becomes more complex (e.g., more dimension on the synthetic data, more complex deep learning model, etc.).

-

Unstructured data

Unstructured data are things like text, pictures, audio, video, etc. These data makes it difficult for people to identify the owner (e.g., a video can contain multiple people’s faces)

The major obstacle to applying DP to these data is the difficulty of identifying a meaningful privacy unit.

Currently, there is very little research on applying DP to unstructured data.

Reduced accuracy amplifying bias

The 3 biases introduced or amplified by DP are:

-

Systemic bias

The smaller a dataset is, the more impact an individual can have on the result.

That’s why when dealing with smaller groups (e.g., minority population), the noise needed for DP is larger than that of others.

This larger noise can significantly impact the outputs of the already small dataset.

In some extreme cases, the noise added to the output can even make a minority group non-existent in a research output.

This would amplify the public bias towards minority populations.

-

Human Bias

What DP can make the output even worse than erasing the entire group is that added noise can make unrealistic results.

E.g.

-

Random noise can be a fractional number, thus making countable measurements (e.g., population) become fractional

-

Random noise can also be larger than the original data (especially when data size and ε are small). Adding negative noise to the output may result in a negative number, which is impossible in measurements like population.

These unrealistic outputs may affect the public’s view towards DP and give them the impression that DP is not a reliable method.

-

-

Statistical Bias

This bias is partly introduced when tackling Human Bias.

When we post-process the DP output to make unrealistic output realistic, the overall accuracy and utility may be affected by the change.

Security challenges

Although the guideline focuses on Differential Privacy, it also reminds us that general security principles also apply to the implementation.

Some of the guidelines given are similar to conventional risk management, but we’ll need to deal with more kinds of vulnerabilities, such as:

-

Interactive Query

Allowing data consumers to run their own queries would make DP implementation difficult because data consumers may be untrusted, and they will try to issue malicious query to break the DP guarantee.

Data custodians also need to store the raw data for real-time queries, which increases data leak risk.

In my opinion, this is similar to conventional application protecting the database behind. But in DP case, we’ll also take Privacy Budget into account.

-

Trust Boundary

The guideline explains 2 different threat models: The local model and the Central model.

Depending on where we put the trust boundary, we will apply DP on different layers, either when data is sent from data subject to data curator, or from data curator to data consumers.

The same principles apply just like when we do the conventional threat model. But in DP case, we also need to balance the output accuracy and risk.

The earlier we apply DP, the fewer risks we take. However, the accuracy of the final output also decreases.

While some challenges may look similar to conventional security frameworks, some are specific to DP.

I’m not going to details because they are quite implementation-specific, but the guideline includes the following:

-

Floating-Point Arithmetic

-

Timing Channels

-

Backend Issues

Back to the basics, data protection is the paramount to privacy protection

Last but not least, the guideline closed up by the 2 most fundamental and yet important things:

-

Data Security and Access Control

-

Data Collection Exposure

Simply put, if we cannot protect the raw data in the first place, all privacy protections would become meaningless.

And take one more step back, data protection and privacy protection can minimize but not eliminate privacy risk.

If the data is not needed for research purposes, we shouldn’t collect it in the first place.